Photographs by Jason Andrew

People look at you differently when you carry a Geiger counter. Or, at least, when you carry a Geiger counter and exclaim things like “Much less radiation here than you might expect!” But how else are you to know that the radiation in your food is at acceptable levels?

They have government inspectors for this, you might say. It is their job.

That was before Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency started hacking away at our bureaucracy. Before the federal government was shut down for much of the fall. And before I bought a Geiger counter to do my own food inspections.

For a while—maybe since 1883, when the Pendleton Act created a merit-based civil service of experts—we, as a nation, thought to ourselves: Life is too short for everyone to inspect their own food. Let the government handle this. But then along came the Trump administration to wonder: What if we didn’t?

FDA inspections at foreign food manufacturers are at historic lows because of staffing cuts, according to ProPublica. My Geiger counter cost $22.79. I thought it would give me a sense of agency and reassurance in this era of dismantlement. Instead, buying the Geiger counter was the first step toward losing my mind.

While the Trump administration conducted a sweeping experiment in government erosion, I started an experiment of my own. As each government function was targeted for cuts—or an official suggested that it was standing between me and my freedom—I put it on my to-do list, as a way to feel like I was doing something other than fretting about what was not being done.

About 300,000 civil servants—roughly 10 percent of the federal workforce—left their job between January and late November last year, according to the Office of Personnel Management. In February 2025, hundreds of weather forecasters and other employees of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were canned. In June, the National Science Foundation was told it had to leave its headquarters. In the fall, during the shutdown, about 1,400 nuclear-security employees were furloughed, and the ranks of air-traffic controllers continued to dwindle.

There is a concept called “mental load”—the weight of knowing all the Things That Need to Get Done Around the House. Someone has to know when to do laundry, take out the trash, buy groceries, locate the winter clothes, cook dinner, set a budget, vacuum, etc. This is the kind of labor that, if not properly divided, ruins marriages and drives people to the brink.

Now multiply that mental load by 343 million. That’s the number of people in the house of America. You can’t worry only about buying the groceries; you must also worry about whether those groceries are radioactive. You don’t just have to make sure the kids are dressed for the weather; you must also forecast the weather. It’s not enough to merely buy eggs; you must also know how much eggs should cost, and what they cost last week, because the economy sort of depends on it.

What became a five-month quest to assume government responsibilities took me from the overgrown fields of Antietam to the cramped basket of a hot-air balloon about 1,400 feet over Ohio; from a biology lab at Johns Hopkins University, where I beheaded flies, to a farmstead in Maryland, where I inspected the fly-bothered udder of a cow named Melissa.

And the potential duties kept piling up as I learned about each round of cuts. Since I started typing this paragraph, Donald Trump has fired many of the people who surveil infectious diseases; before I finish typing this paragraph, he may have hired them back. I hope so! I would do almost anything for a good story, but perhaps I should draw the line at “monitor Ebola.”

John F. Kennedy famously implored us: “Ask not what your country can do for you—ask what you can do for your country.” Well, I asked! And the answer is: lots of things. If you don’t mind doing them wrong.

1. I FORECAST THE WEATHER

I have just driven six and a half hours to Ohio in order to forecast my own weather. From a hot-air balloon.

“Anyone that tells you they’re not afraid of heights is either lying or insane,” Tim the balloon pilot is telling me. It is 5 p.m. on a clear Tuesday in September, and we are getting ready, in a field outside Columbus, to go up and find weather. Tim has a trim white beard and a confident demeanor that I find reassuring. There are two kinds of balloonists, Tim tells me: old ones and bold ones. He is the former.

Weather forecasting is among the legion of chores that the government does, or used to do more thoroughly, through NOAA, whose budget the Trump administration attempted to slash—a scenario that would “stop all progress” in U.S. forecasting, as James Franklin, a former branch chief at the National Hurricane Center, told USA Today.

In the founding days of the country, individuals collected weather data alone, without the aid of computers, weather balloons, or modeling. George Washington kept a fairly detailed weather diary. Behold his entry for April 14, 1787: “Mercury at 62 in the Morning—74 at Noon and 68 at Night. Cloudy in the Morning with a few drops of rain.” But while journaling is fine if you want to know what the weather was, most people want to know what the weather will be. For that, you need other people.

The advent of the telegraph allowed weather watchers to share observations and data across great distances, in almost real time. This launched the era of forecasts—or, as the pioneering meteorologist Cleveland Abbe called them, “probabilities.” Cleveland left his home base of Cincinnati (just to confuse you!) to work for an arm of the federal government that would later become the National Weather Service.

“The nation has had few more useful servants than Cleveland Abbe,” the meteorologist Thomas Corwin Mendenhall wrote around 1919, praising his storm warnings, which saved millions of dollars’ worth of property every year.

Human observation and telegraph chitchat were eventually supplanted by radiosondes, which are sensor packages launched by balloon twice a day, all across the country, to determine wind direction, temperature, pressure, and so on. After DOGE cuts in February, several sites pared back to one launch a day; the Alaskan cities of Kotzebue (along the western coast) and St. Paul (out in the Bering Sea) stopped launches altogether.

I had asked Keith Seitter, a senior policy fellow at the American Meteorological Society, how I could forecast weather myself, without using government models. He made the mistake of suggesting that weather generally travels west to east at a rate of 20 to 30 miles an hour. I latched on to this. Could I simply find a city that is about 500 miles west and drive there to get tomorrow’s weather today?

Well, sure, Keith said, but that seems like a big waste of time.

Please! I have two children under the age of 4. I have nothing but time.

I Googled my way to Tim and his hot-air-balloon company in Columbus. It had a single review on Yelp, from 2012, but that review was five stars: “Tim is a great pilot.” Good enough for me!

I meet Tim and his crew in a parking lot near a golf course. We pile into his balloon van, with the balloon basket attached to the back, and drive to our takeoff point. The basket is stunningly small—more like a double-wide grocery cart. We arrive at 5:37 p.m., just as the sun is starting to slide toward the horizon.

The Geiger count in Ohio is a tiny bit lower than in Washington, D.C., if you were wondering. But my instrument now is a combination thermometer-barometer-anemometer that I bought for $22.89.

Tim reassures me that “the vast majority of people in a balloon don’t realize any sensation of height issues,” because “balloons use natural forces.” I thought gravity was a natural force? I am becoming agitated. Tim, in our initial call, described some balloon landings as “sporty,” an adjective I do not like having applied to my physical safety.

Listen. I am actually very afraid of heights. I always forget this until I am irretrievably committed to a course of action that will take me to the top of a height, and then, as I am borne ineluctably to the top of that height, I think, Oh, right. I am terrified of these.

I hoist myself over the edge of the basket. My palms are sweating. Suddenly everything around us becomes very small. There is a miniature tractor doing neat laps around a miniature field. A hawk is … below us?

“Very high was a mistake” is what my notes say at this point.

My phone has acquired a thin film of sweat, maybe from condensation? 29.06 on the barometer. 85.3 degrees Fahrenheit. It is eerily quiet except for the periodic firing of the propane tank, which sounds like someone is grilling very urgently right in my ear. 28.26, 87.3 F. The temperature is suddenly much cooler: 47.3 degrees, although it doesn’t feel like that at all.

Then I realize that I have been reading the dew point instead of the temperature.

When I switch to the actual temperature, I realize a second problem: Whenever Tim fires the burner, the basket of the balloon becomes hot. It is like being aloft with a small campfire. Now, instead of telling me that it is 52.9 degrees, my thermometer informs me that it is 91.2 degrees! It is a beautiful, still, cloudless evening. If only Cleveland Abbe could see me now! He would probably say something like “What a senseless waste of astonishingly futuristic equipment.”

We drift over more fields and hummers, which is what some balloonists call power lines. Below us: trees, fields, houses, old junked cars, the occasional dog.

Our descent is not at all sporty, although I hold my breath as we approach the hummers. Tim has done this 1,600 times, and thus we do not fly into a power line, or you would not be reading this. It turns out that in this business, you just sort of … land in people’s yards? Members of the balloon crew have had guns pulled on them before, and dogs unleashed.

Improbably, the yard we land in belongs to a proud Atlantic subscriber named Deborah, who is apparently a competitive pinball player. I try to explain why we landed in her yard, making Deborah the first of many strangers to be confused by my project. Deborah is nonetheless so excited by my affiliation with The Atlantic that she asks for a hug. For a subscriber, anything!

On the ground it is 7:18 p.m., somewhere between 78.3 and 80.8 degrees. I cannot stress enough how lovely this weather is. Clear and crisp and the perfect temperature, the kind of fall day you order from an L.L. Bean catalog.

The next day, I begin my easy, convenient, six-plus-hour drive home to see my weather.

I close in on D.C. and notice it is raining. The sky is gray. Gray gray gray.

This is not my weather! I did not drive all the way from Ohio to bring this! I DON’T KNOW THIS WEATHER!

A friend whose hobby is meteorology informs me that current pressure systems are making the weather travel from east to west today. Whoops.

There is a certain indignity in having done this astoundingly inefficient thing and not even gotten the weather right at the end of it. So for my next government function, I will try something that involves no data collection. The only thing at stake? The safety of myself and my family.

2. I INSPECT MY OWN MILK

We currently do not have a Senate-confirmed surgeon general, who is supposed to be the “nation’s doctor.” But the president’s nominee for the role, Casey Means, has offered food-related advice for cutting the government out of your life. She is more of a doctor than I am (in that she finished medical school) but less of a doctor than you might want the nation’s doctor to be (in that she didn’t complete her residency and decided to get really into “good energy”). The week after the 2024 election, Means said something interesting about raw milk, in the context of burdensome government regulation, on Real Time With Bill Maher.

“I want to be able to form a relationship with a local farmer,” Means said, “understand his integrity, look him in the eyes, pet his cow, and then understand if I can drink his milk.”

Thus, I am at a farm in southern Maryland to do just that. The difficulty with raw milk is that it isn’t always legal to sell for human consumption. Fortunately, this farm sells allegedly delicious “pet milk” (wink, wink). It also gives its cows operatic names, such as Tosca, Traviata, and Renee Fleming. I have asked for permission to put Casey Means’s vision into practice here.

A farmer named Brian takes me to the cows, past the egg layers and the meat chickens, bivouacked in what he tells me are excellent conditions in a nearby field. (“Raise me this way and you can slaughter me too!” Farmer Brian says.)

In preparation for this visit, I spoke with a veterinarian, who told me how to assess the health of a cow. The vet said that I should be able to see some of the cow’s 13 sets of ribs, but not too many. The cow should not be oddly hunched. Its udder should be long and pendulous.

Brian introduces me to Melissa, who is named for a singer.

“Etheridge?” I ask.

Brian laughs. No further information on Melissa’s surname is forthcoming.

Melissa just stands there, covered in flies.

“Flies help clean them up,” Farmer Brian tells me. Is this true? I add it to a growing list of Things I Am Not Sure Are Facts.

It used to be that milk only came raw, and everyone had to decide for themselves whether to drink it. The penalty for drinking subpar milk was that you died. In the 19th century, this happened fairly often, especially to American children. Then we discovered that diseases were caused by microorganisms. Tuberculosis, scarlet and typhoid fevers, diphtheria, brucellosis—all of these could be transmitted by milk.

At the urging of President Theodore Roosevelt, fresh off the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, a commission of public-health officers put out a 751-page report tracing recent outbreaks to contaminated milk. Milk was a wonderful environment for germs to grow in. Some of them could join your gut microbiome as helpful allies; others could give you deadly diarrhea. Instead of rolling the dice, the report made the case for pasteurizing milk—that is, heating it—to kill harmful microorganisms.

Making milk safe to drink was one of the greatest public-health breakthroughs in history. “For every 2 billion servings of pasteurized milk or milk products consumed in the U.S., only about one person gets sick,” the FDA reports.

I’ve been especially leery of diseases lately. FoodNet—the CDC’s Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network—is scaling back the germs it tracks, from eight to two (salmonella and one type of E. coli ). I guess we want listeria to come as more of a surprise. And now followers of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement are encouraging us to drink the kind of milk that we stopped drinking around 1924 because it was too risky.

Anyway, back to Melissa. She has horns. This is good, Farmer Brian says, because “horns are the antennae, and all the cosmic energy comes down in through the horns.” I add this to my list of Things I Am Not Sure Are Facts.

How long does this milk keep? “It doesn’t go bad,” Farmer Brian says. This feels famously untrue of milk. “If you’re on the standard American diet, it will give you the runs,” Farmer Brian admits.

I tentatively ask why this milk seems so much more shelf-stable than the milk I myself have been producing for my infant, which can last in the refrigerator for only four days. Brian seems puzzled by this, and hands me 13 pamphlets, including “Cod Liver Oil: Our Number One Superfood” and “After Raw Breast Milk, What’s Best?” They do not answer my question.

I pause in the farm’s gift shop, which has folk-music CDs, hats made out of alpaca wool, and books explaining why COVID was not caused by a virus (“are electro-smog, toxic living conditions, and 5G actually to blame?”). I had better buy some milk, I guess.

I bring the milk home and stare at it. It is in a plastic jug, with a label that says NOT FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION. I am starting to miss the government. It used to be that when I brought milk home, I could drink it. Now I have to do all of this research.

I leave the milk on the counter overnight. My husband wants to throw it out, on the grounds that it is confusing and growing stinky, but I explain that I am writing about it, and that we do not throw out the U.S. economy and politics (what he writes about) because they are confusing and growing stinky.

To make myself more comfortable with the milk on my counter, I read studies. The more I read, the more I am discouraged. A study from 2017 says that 96 percent of illnesses caused by contaminated dairy came from raw milk and cheese. I don’t like those odds.

I enjoyed petting Melissa and looking Farmer Brian in the eyes. But I don’t think that gave me the information I needed to understand whether I could drink the milk. What I should have done was scan the milk for microorganisms or simply boil it. In the time it has taken to figure this out, the milk has turned a cloudy yellow and formed three distinct strata.

Months later, I still have not thrown it away, or opened it. I am hoping that if I procrastinate long enough, it will simply become cheese.

3. I COLLECT CONSUMER PRICES

I’m darting through grocery stores across D.C., trying to get someone to help me nail down the price of eggs over time. I have to get better at economic-data collection quickly, because the Trump administration is targeting the Bureau of Labor Statistics. You might wail something like: Who cares about the most bureaucratic-sounding bureau, at a time like this?

I do. I am becoming more of the government, every day, and it is going great.

The BLS is an attempt, through relentless data collection, to get everyone a nice set of shared facts about the economy and the workforce. Are there enough jobs to go around? The BLS puts out a monthly jobs report (though it missed October because of the shutdown). How far does your paycheck go? The BLS tabulates the Consumer Price Index, which identifies All the Things That People Buy and then figures out if they cost more or less than they used to. In essence—since 1884, when it was the Bureau of Labor—the BLS takes pictures of the economy for us.

But the pictures have not been very flattering lately, and so the Trump administration has responded by trying to smash the camera. After the July jobs report did not have enough jobs, the president fired the BLS commissioner. Trump’s 2026 budget proposes an 8 percent cut to the BLS budget. And DOGE’s hacking at the BLS may have contributed to a suspension of data collection in three cities: Buffalo, New York; Provo, Utah; and Lincoln, Nebraska.

To collect my own economic data, I need to become a “first-rate noticer,” says Jay Mousa, a former associate commissioner for the BLS office of field operations. That is part of what BLS field economists do. They are an army of perceptive extroverts who go from place to place, look around, talk with people, and find out what they are paying or charging for goods and services.

Mousa suggests that I go from store to store and find out the price of an item, now and in the past. Finding out the current price seems doable. But the past price? I could ask employees, he suggests. Perfect! I will use my thing-noticing, people-coaxing skills, just like a real BLS field economist.

Glancing at the dozens of items priced by the BLS in its list of average retail prices, I select eggs (one dozen, large, grade A). Eggs feel very present. They were the thing, during the 2024 election cycle, that people said cost too much, and now look where the country is.

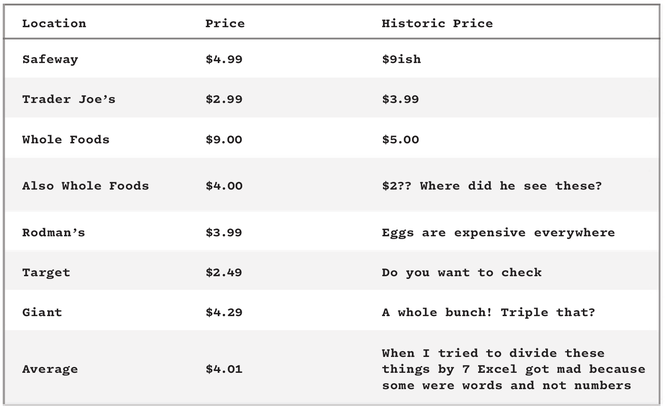

I begin at a Safeway, asking a cashier what eggs cost now and what they cost earlier in the month. The clerk reports that eggs cost $4.99 a dozen, and remembers that they used to be a lot more expensive, like nine-something dollars. I feel awkward enough about this exchange that I buy the eggs. Did I collect data, or did I just go grocery shopping?

At Trader Joe’s, I stare at a sample cup of butternut-squash mac and cheese before knocking it back like a shot. Then I notice that I am being offered a fork. First-rate noticing! A cardboard gargoyle peers down at me from the corner of the store. “That is a gargoyle,” I say, trying to ease myself into conversation with the employee who offered me the mac and cheese.

“It’s cardboard,” the employee says. “It has been there five years.”

I ask him about the historic price of eggs and he says that the cost has gone down—eggs that are $2.99 were $3.99 a mere two days ago! A secret weekend egg deal? Like a real field economist might find? He doesn’t know. I leave the store with two specific numbers and without buying anything, which I consider a double win. Plus, I have data on the longevity of the cardboard gargoyle, just in case.

“I can’t help but notice we are in a Whole Foods,” I tell a Whole Foods employee who—perhaps having noticed me walking around with no shopping cart and a Geiger counter—has asked if I need help. “Is there any way of finding out what eggs used to cost in the past?”

He tells me that they have roughly doubled in price—eggs that are now $9 a carton were once $5; those that are now $4 were once $2.

These are the peaks of my data collection. At Giant, I am informed that eggs used to cost triple what they cost now. At Rodman’s, when I ask what eggs used to cost, all I get is the assurance that eggs are expensive everywhere. At Target, an employee responds to my inquiry about the historic price of eggs by asking if I want to go to the egg aisle and see for myself. “No,” I say, “I meant in the past.” I complete the rest of my self-checkout in silence.

I need something to show for this effort. So I make a table using the data that I collected for a dozen large eggs, grade A.

This takes me only three hours. Should I be averaging the variables? That feels like a thing I can do. Can you average a number ending in ish ?

Maybe it’s better not to collect too much economic data. Maybe doing so would frighten the economy. Maybe I’d better do something that can only help the economy: basic scientific research, which can ripple into world-changing breakthroughs. Did you know that studying the venom of gila monsters—decades ago, at a Veterans Affairs medical center—yielded a treatment for type 2 diabetes that, in the past few years, has spawned a weight-loss revolution?

And so I drive to Johns Hopkins University, where I hear they do a lot of science.

4. I DO MY OWN RESEARCH

I have just destroyed eight human retinal organoids with my subpar pipetting.

Allie—a grad student in Professor Bob’s biology lab here at Johns Hopkins—is being very nice about it, but I feel terrible. She needs these retinas so she can study how different photoreceptors are made.

Johns Hopkins, “America’s first research university,” receives a lot of government funding. Or, at least, it used to. Something like $3 billion in grants were cut last year across the National Science Foundation and the NIH. When USAID was dismantled, Johns Hopkins lost $800 million in grants, leading to the elimination of more than 2,200 jobs around the world.

In Professor Bob’s lab, grad students are trying to figure out how genes are expressed and how that affects an organism’s physiology. Flies are helping them understand this by dying in large quantities. These are special flies whose genotype we know a lot about, and they live in jars full of a special sugary food, which they consume contentedly for their entire life (about 45 days).

They (the researchers, not the flies) suggest that I start small. My task will be to help flip the flies—move them from one jar full of a dense sugary substance to another jar—without releasing too many. Then I get to sex the flies, and then, with a microscope and forceps, I get to behead them. This is the closest I will ever get to being a praying mantis. The grad students report that informing people of the sex of nearby flies is a fun trick they perform at parties. (Gen Z needs to drink more.)

The percentage of the federal budget that goes to general science and basic research is not huge—about 0.2 percent—unless you consider the F-35 fighter jet a form of science. But the return is astounding. Google’s beginnings can be traced to a federal grant for digital libraries. Now look at the company, helping to keep the entire economy afloat—and leading me to Tim the balloon pilot!

“Without scientific progress,” the eminent engineer Vannevar Bush (also an eminent Atlantic writer) once wrote, “no amount of achievement in other directions can insure our health, prosperity, and security as a nation in the modern world.” He submitted a report to Harry Truman in 1945 to argue for creating an agency that could support and fund basic research around the country. His brainchild, the National Science Foundation, was born in 1950. Dedicated support for scientific research has given us GPS (where would we be without it?), cancer-research funding that’s helped save millions of lives (something we used to agree was an obvious good), and the atomic bomb (a parenthetical aside is the wrong venue to sum up my feelings about the atomic bomb).

So those are the stakes. Just millions of lives, the entire economy, and, of course, our health, prosperity, and security as a nation in the modern world.

I have to focus! My next task is to help grow human retinal organoids, for study. Grad Student Allie does this by starting out with a set of stem cells and then using chemicals to insist that those cells become retinas. She shows me the ones she has been working on, all in various stages of development. The newest ones resemble leaves with little nibbles around the edges; the more mature ones have become blobs with little meatballs attached; later, she removes the meatballs and, presto, a retina. To me, this is functionally witchcraft.

I do my best to help her in the earlier stages of retina development, by extracting waste from vials with growing retinas and then pipetting in pink liquid (food? Do baby retinas eat?).

I extract something that I hope is waste and gently squirt it into a waste container. Whatever it is, I guess it’s waste now. Then I use the pipette to draw up a quantity of pink liquid and squirt it into the tube. I do this slowly and carefully, in the same way that I drive slowly and carefully: in little, jagged bursts of speed, interrupted by long pauses. This is not ideal pipetting. Bubbles form. Retinas are destroyed.

Allie is very kind, despite the devastation I have wrought. I won’t be able to replicate this at home, anyway. I don’t have any stem cells—unless some are growing between the yellow strata in my jug of raw milk that might soon become cheese?

5. I BEGIN TO LOSE MY MIND

I am starting to unravel a little bit. Becoming aware of all of these things I did not formerly think about has only made me aware of even more things.

The Corporation for Public Broadcasting took a hit—perhaps I should make children’s programming?

Cuts to the IRS? I’ve got to audit things! Does anyone know a billionaire willing to share his tax records with me?

The U.S. Geological Survey’s budget might be cut by almost 40 percent. WHERE IS THE OCEAN? GET ME A MEASURING TAPE!

Did I mention that the first hot-air-balloon ride I booked—before I found Tim in Columbus—charged my credit card twice and sent me to a Cincinnati rendezvous point where no one showed up? No balloon, no balloon pilot, nothing! Does the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau investigate balloon fraud? If it does, it probably won’t for much longer. Trump is trying to shut down the bureau.

Bridge inspectors at the Department of Transportation are still on the job, but maybe I should familiarize myself with the varieties of truss.

Who’s watching all of the airplanes? I play the simple games for aspiring air-traffic controllers that NASA (not the FAA, curiously) hosts on its website. These games offer all the fun of basic trigonometry, plus an ominous announcement, if you get the math wrong, reading, “SEPARATION LOST”—an aviation reference for occasioning a mid-air collision.

All the while, I have my Geiger counter, which is now a dear old friend, having stuck with me through it all. But what happens if I find actual radioactive material? My knowledgeable friends suggest vitrification, which can turn liquid waste into solid waste, because solid waste is much easier to deal with than liquid waste (as a parent of two young children, I can confirm). Unfortunately I do not have good vitrifying equipment in my kitchen.

I catch my husband Googling what price divorce, but he assures me it is just to help with my BLS research. Also, I made the mistake of telling my 3-year-old that I stepped in cow dung at the farm, and now every time she gets into the car, she claims that it “smells poopy.”

I’m tired of asking what I can do for my country! I’ll just go for a soothing walk.

But taking a soothing walk reminds me that the National Park Service, too, is suffering cuts; 24 percent of its permanent workforce is gone. But I don’t know how to help. I thought that maybe I could clean toilets on the National Mall; an internal NPS spreadsheet listed Areas Where It Was Stretched Thin, including bathroom maintenance. But when I poke my head in the stalls, the bathrooms around the Washington Monument seem just fine. Maybe everything’s just fine!

I think about offering my interpretive services at the World War I Memorial, but the plaques there imply that every day at 5 p.m., the actor Gary Sinise sends a bugler to play taps, and I don’t want to compete with Gary Sinise’s bugler.

I read in the same NPS spreadsheet that the Antietam battlefield has curbed its mowing and is “less-than-manicured,” which “may be viewed negatively by visitors.” Perhaps this is how I can help. I will go to the place that saw the bloodiest day of the Civil War and see what needs doing. Maybe I can tidy up? And maybe I can finally feel like I’m doing something for my country.

6. I DO YARD WORK AT ANTIETAM

I am scrabbling in the dirt with my bare hands in Antietam National Battlefield, trying to clear a walking path around a felled tree. “I don’t think I’m helping!” I say, for the fifth or sixth time, to the photographer who is documenting my civic-minded humiliation. I am sweating. There is dirt under my nails and dirt in my boots. I have moved what feels like a lot of dirt around, but also I have not moved enough dirt around. The path is still blocked.

It is October. It is lovely in the autumn way of clear water moving over rocks as leaves fall. Antietam is the name of a creek, and something about the creek’s scale feels wrong, given what happened here 164 years ago. Too small, somehow. Suspiciously still.

I don’t know what else to do, in this current chapter of American turmoil, so I am doing this: clearing a path, because there ought to be a path here.

This task would be easy for a person with the right equipment. It would take an hour for someone with a chainsaw. But I am trying my best, and my best is no good at all.

“You have perhaps believed Government jobs to be ‘soft’ and ‘easy,’ ” Horace M. Albright, the superintendent of Yellowstone, wrote to park-ranger applicants in the summer of 1926. “Most of them are not, and certainly there are no such jobs in the National Park Service.”

The hard work of the park rangers at Antietam is to protect this place of history for visitors in the future. Antietam was brutal, with thousands of casualties—among them, arguably, slavery. After the battle, Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring the end of slavery in the Confederate states. The bloodshed at Antietam helped extend the promises of the Declaration of Independence to more people.

The site needs to be preserved. It needs to be kept sightly. It needs … to be mowed.

I see some unkempt grass near a few cannons and get my friend Dave’s hand mower out of my trunk. The moment when you push a hand mower around Antietam is a moment when you must ask yourself questions, such as: How did I get here? How did we get here?

How I got here: a five-month experiment in self-government as an individual.

How we got here: a 250-year experiment in self-government as a group.

I push the mower forward, and think about truths that are self-evident. The world is full of threats to life and liberty, before you even start thinking about the pursuit of happiness. If you want to have life, that means you want to be able to buy a sandwich, take a bite out of it, and not die. You want your children to drink milk and not die. If a big storm is coming, you want to know about it so you can evacuate if you need to. Where there is nuclear waste, you want it put away properly. You want to increase your sum total of knowledge about the human body and the world, so that you can prevent disease, or cure it. And, ideally, you want passionate citizens to handle the specialized stuff—people who love flies, or dew points, or the price of eggs, or making sure airplanes don’t hit each other.

If there were a big button that said, “Hey, push this button and somebody else will handle all the hard, technical stuff, and in exchange you will pay a percentage of your annual income, but don’t worry: We will have a team of people to make sure that you pay the right amount; also, there will be large, beautiful places where you can go for walks and learn about nature and history. And all the time you save will be your own!,” I would absolutely push that button.

But for now, I push the mower.

People have tried to walk away from the federal government before. To break it up. And on this hill that I am mowing, some men died saying, “No. You don’t get to do that. You’re in this with us.”

When I think of civil servants in this current uncivil moment—the air-traffic controllers who worked during the shutdown; the NOAA weather chasers flying into a hurricane to measure it, paycheck or no paycheck; the Park Service employees scrambling to keep bathrooms clean despite the cuts to their ranks—I will now think of Antietam.

I asked what I could do for my country and the answer was: alone, not much. Indeed, many things are weird at best, or destructive at worst, when you try to do them yourself. But if enough people get together and commit to doing them, you’ve got yourself a government.

Together, it’s doable.

Alone, I give up!

Time to drive home from Antietam. Having mowed slightly, and been humbled greatly, I declare my experiment in self-government to be over. Save for one final task.

I’ve got a glass of cheese to drink.

This article appears in the February 2026 print edition with the headline “I’m Not From the Government but I’m Here to Help.”