On November 2, White House chief of staff Susie Wiles told Vanity Fair that land strikes in Venezuela would require the approval of Congress.

She said if Donald Trump "were to authorise some activity on land, then it's war, then (we'd need) Congress".

Days later, Trump administration officials privately told members of Congress much the same thing – that they lacked the legal justification to support attacks against any land targets in Venezuela.

READ MORE: Venezuela's vice president says country will never be a US colony

Just two months later, though, the Trump administration has done what it previously indicated it couldn't.

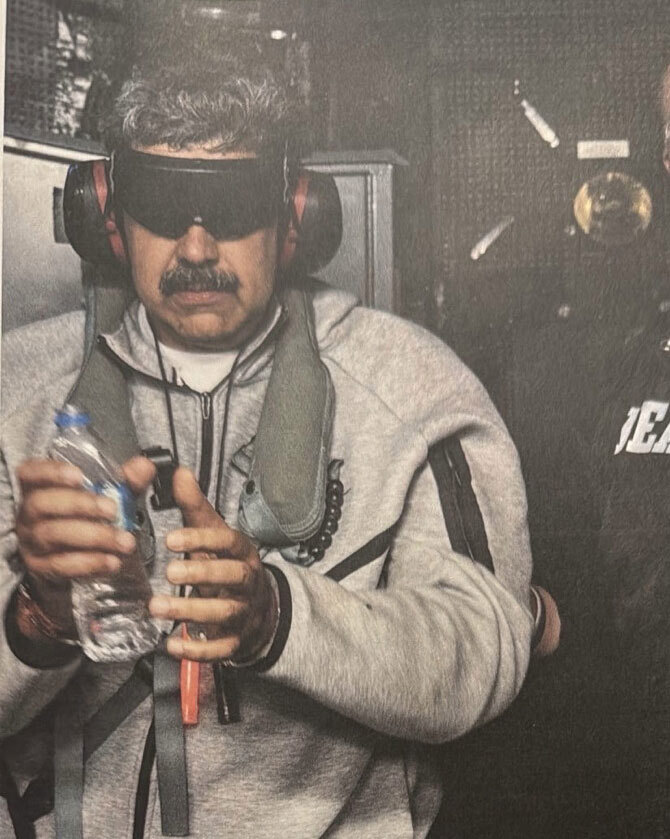

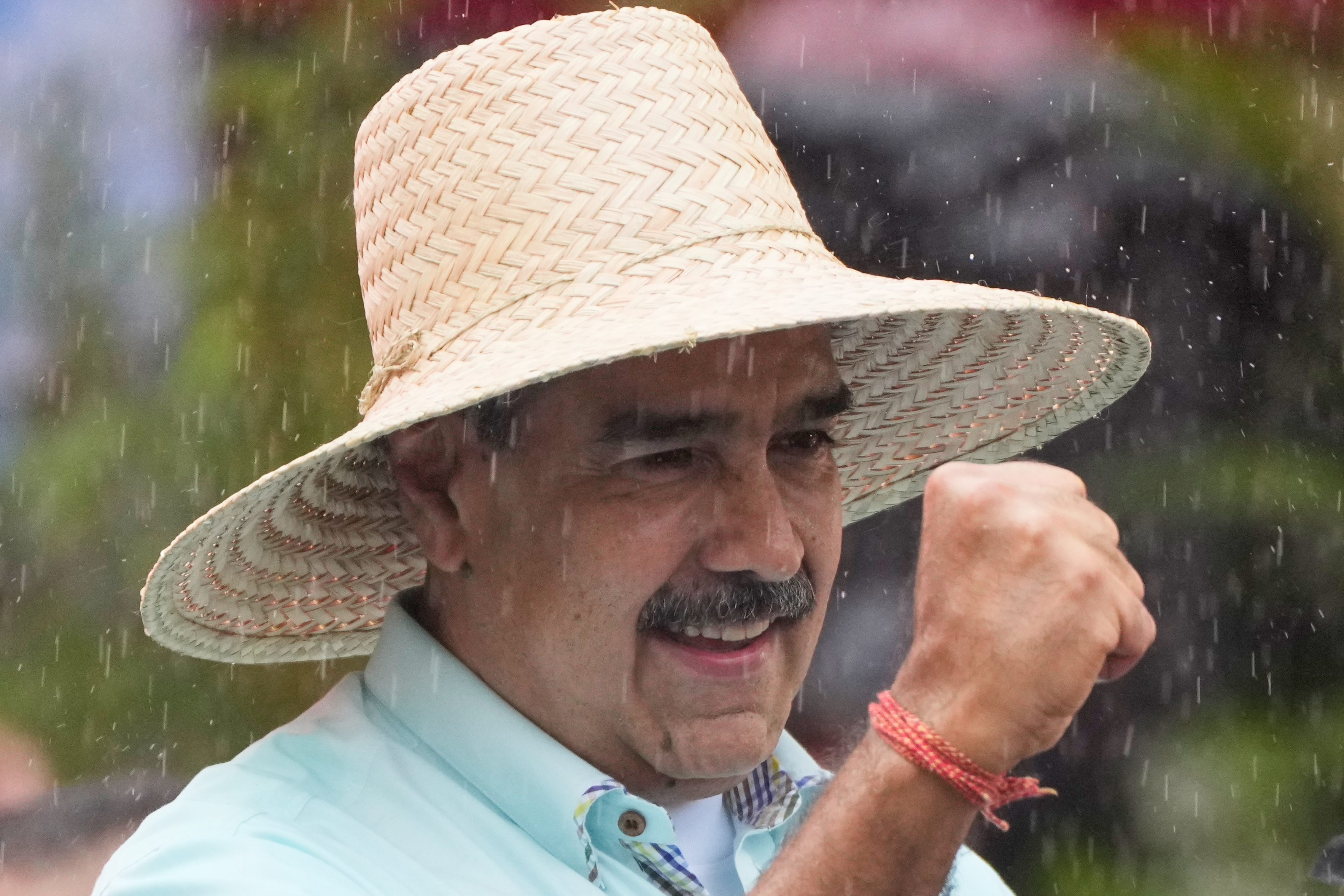

It launched what Trump called a "large scale strike against Venezuela" and captured its president, Nicolas Maduro, to face charges. And it launched this regime change effort without the approval of Congress.

(Trump in November claimed he didn't need congressional authorisation for land action, but it clearly wasn't the consensus view in the administration.)

It appears the mission is, for now, limited to removing Maduro.

But as Trump noted, it did involve striking inside the country – the same circumstance some in the administration previously indicated required authorisation that it didn't have.

CNN reported in early November that the administration was seeking a new legal opinion from the Justice Department for such strikes.

And Trump in a news conference spoke repeatedly about not just arresting Maduro, but also running Venezuela and taking over its oil – comments that could certainly be understood to suggest this was about more than arresting Maduro.

Legally dubious strikes inside another country – even ones narrowly tailored at removing a foreign leader – are hardly unheard of in recent American history.

But even in that context, this one is remarkable.

READ MORE: Why is the US attacking Venezuela?

Shifting justifications

That's because the Trump administration has taken remarkably little care to offer a consistent set of justifications or a legal framework for the attack.

And it doesn't even appear to have notified Congress ahead of time, which is generally the bare minimum in such circumstances.

A full explanation of the claimed justification has yet to be issued, but the early signs are characteristically confusing.

Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah said shortly after the strikes that Secretary of State Marco Rubio told him the attack was needed to, in Lee's words, "protect and defend those executing the arrest warrant" against Maduro.

"This action likely falls within the president's inherent authority under Article II of the Constitution to protect US personnel from an actual or imminent attack," Lee, a frequent critic of unauthorised foreign military action, said.

Hours later, Vice President JD Vance echoed that line.

"And PSA for everyone saying this was 'illegal': Maduro has multiple indictments in the United States for narcoterrorism," Vance said on X.

"You don't get to avoid justice for drug trafficking in the United States because you live in a palace in Caracas."

At a later news conference, Rubio echoed the line that the military had been supporting "a law enforcement function."

But there are many people living in other countries that are under indictment in the United States; it is not the US government's usual course to launch strikes on foreign countries to bring them to justice.

The administration also hadn't previously indicated that military force could be legally used for this reason.

Initially, Trump threatened land strikes inside Venezuela to target drug traffickers – this despite Venezuela being an apparently somewhat small player in the drug-trafficking game.

Later, the administration suggested strikes might be needed because Venezuela sent bad people into the United States.

And then, after initially downplaying the role of oil in the US pressure campaign against Venezuela and Maduro, Trump said he aimed to reclaim "the oil, land, and other assets that they previously stole from us."

The signals were confusing enough that even the hawkish Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina in mid-December indicated the administration lacked "clarity" in its messaging.

"I want clarity right here," Graham said.

READ MORE: US captures Venezuela's president and wife, removes them from the country

"President Trump is saying his days are numbered. That seems to me that he's gotta go. If it's the goal of taking him out because he's a threat to our country, then say it. And what happens next? Don't you think most people want to know that?"

Despite the focus on the law enforcement operation, Trump at the news conference said the United States would now participate in running Venezuela, at least temporarily. And he repeatedly spoke about its oil.

"We're going to rebuild the oil infrastructure," Trump said, adding at another point: "We're going to run the country right."

And even if the administration had offered a more consistent justification, that doesn't mean it would be an appropriate one.

A controversial 1989 memo

The most recent major example of using the US military for regime change is the war in Iraq.

That war was authorised by Congress in 2002. The broader war on terror was authorised by Congress in 2001, after the 9/11 attacks.

Since then, administrations have sought to justify several military actions in the Middle East using those authorisations – sometimes dubiously.

But Venezuela is in an entirely different theatre.

While many have compared the effort in Venezuela to Iraq, the better comparison – and one the administration apparently intends to make – is Panama in 1989.

Like in Venezuela, Panama's leader at the time, Manuel Noriega, was under US indictment, including for drug-trafficking. And like in Venezuela, the operation was less a large-scale war than a narrowly tailored effort to remove the leader from power.

The Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel in 1980 had concluded that the FBI didn't have the authority to apprehend and abduct a foreign national to face justice. But George H.W. Bush administration's OLC quietly reversed that in the summer of 1989.

READ MORE: Who is Nicolas Maduro? From bus driver to Venezuela president

A memo written by William P. Barr, who would later become attorney general in that Bush administration and Trump's first administration, said a president had "inherent constitutional authority" to order the FBI to take people into custody in foreign countries, even if it violated international law to do so.

That memo was soon used to justify the operation to remove Noriega. (As it happens, Noriega was captured January 3, 1990.)

But that memo remains controversial to this day. It's also an extraordinarily broad grant of authority, potentially allowing US military force anywhere

And the situation in Venezuela could differ in that it's a larger country that could prove tougher to control with its leader in foreign custody. It also has significant oil wealth, meaning other countries could take an interest in what happens there next. (China has called the attack a "blatant use of force against a sovereign state".)

In both the news conference and an interview with Fox News, Trump invoked the possibility of further military option, reinforcing that this could be about more than just arresting Maduro.

That also means the questions about Trump's legal authorities could again be tested – just as he's already tested them with his legally dubious strikes on alleged drug boats and other actions in the region.

What's clear is that Trump is seeking to yet again test the limits of his authority as president – and Americans' tolerance for it. But this time he's doing it on one of the biggest stages yet.

And the story of his stretching of the law certainly isn't over.