This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

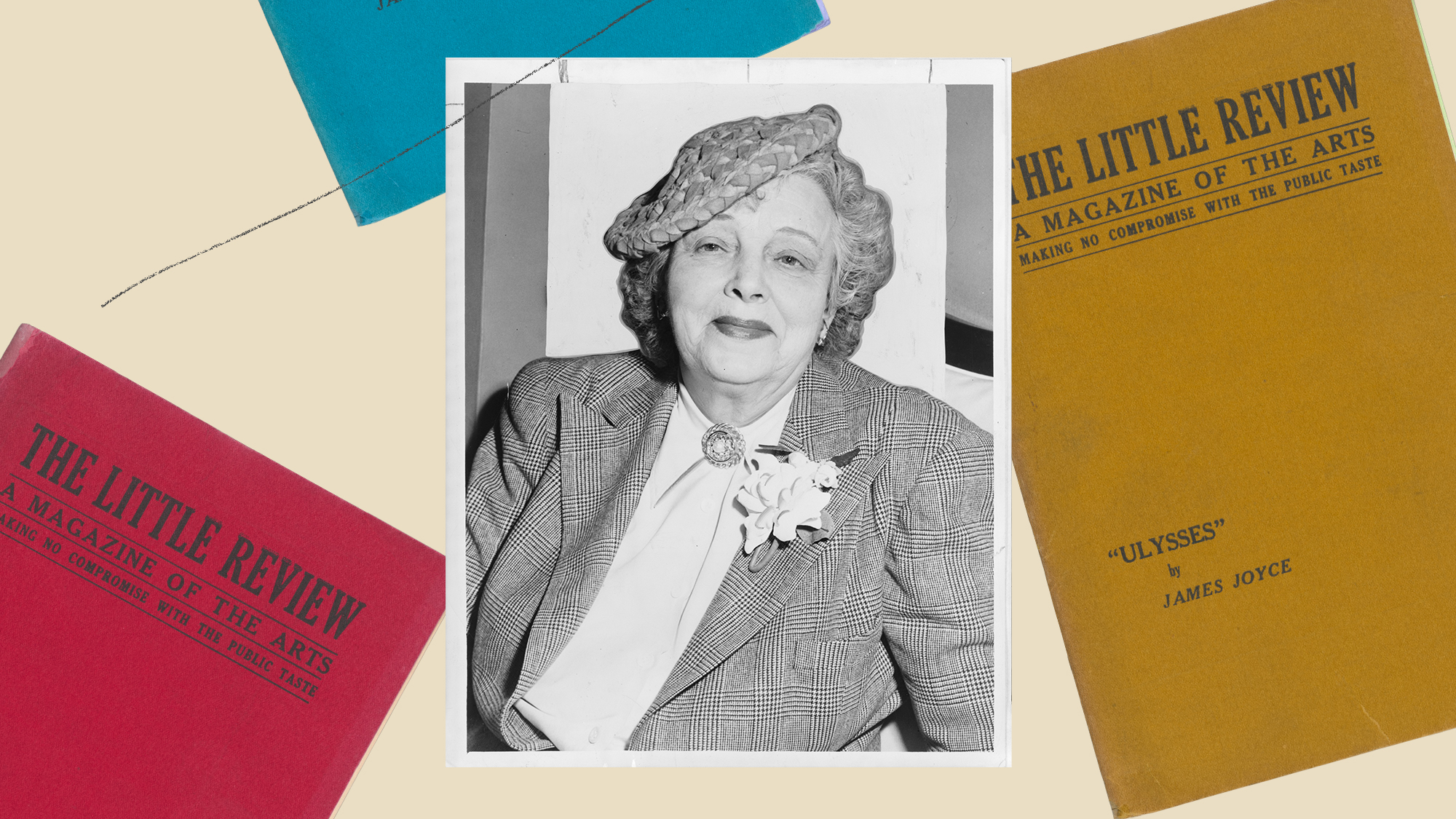

In a recent Atlantic article about Adam Morgan’s new book, A Danger to the Minds of Young Girls, Sophia Stewart poses a choice that many biographers struggle with: “what to do with the boring bits.” This feels like an apt dilemma to invoke while critiquing a book about an editor. Morgan’s subject, Margaret Anderson, was the first person to publish portions of James Joyce’s Ulysses in the United States—and was convicted on obscenity charges as a result. But as Stewart writes, Anderson, who founded The Little Review in 1914, was an editor for less than 10 years, and afterward she lived “the way most people do, somewhat aimlessly.” Because of this, Stewart believes, the biography falls short of its promise; Morgan fails to prove his argument that Anderson’s “greatest work” was “the life she had forged” after leaving her career. Perhaps, she suggests, he should have focused on the editing—and edited out the boring bits.

First, here are four stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- George Saunders has a new mantra

- A novel about the costs of family secrets

- Why so many writers are athletes

- “I am here in the evening light,” a poem by Issa Quincy

Morgan’s book is the latest in a series of recent biographies that set out, as Stewart writes, to anoint editors including Malcolm Cowley, Judith Jones, and Bennett Cerf “as the unsung architects of the American literary canon.” The editor-biography I would most recommend is far older than the new crop, and it shows the benefits of a tight focus on the work—rather than the life—of its brilliant subject.

A. Scott Berg begins his 1978 biography, Max Perkins: Editor of Genius, by describing what Perkins, a legendary editor at Scribner, did for his authors: “He helped them structure their books, if help was needed; thought up titles, invented plots; he served as psychoanalyst, lovelorn advisor, marriage counselor, career manager, money-lender. Few editors before him had done so much work on manuscripts, yet he was always faithful to his credo, ‘The Book belongs to the author.’” Following through on this opening, Berg illustrates in minute detail the way Perkins managed to act in all these capacities, turning piles of paper into great American novels such as The Great Gatsby and A Farewell to Arms.

“Are biographers storytellers or annalists?” Stewart asks in her piece. “The best of them combine the two vocations.” Berg certainly does; his manner of focusing wasn’t to pare away information, but instead to dig deep into the archives. Because his subject was surrounded by colorful and often unpredictable characters—alcoholics, neurotics, and blowhards—Perkins’s self-effacing qualities make for a dramatic contrast and a wealth of wild stories. And because Perkins’s work was painstaking, Berg’s research was exhaustive. It took many interviews and manuscript analyses to emerge with a narrative that proves that Perkins didn’t only edit geniuses, but was one. And it’s rarely boring to watch a genius at work.

Berg did one more thing right. The first important choice a biographer must make is the same one an editor confronts: Pick the most promising project. This sometimes means an exciting or popular figure, but it can also mean an enigmatic character whose accomplishments (and associates) compel intense curiosity. Max Perkins, Berg’s first book, won a National Book Award. He went on to write biographies of Charles Lindbergh, Katharine Hepburn, and Woodrow Wilson; all these works were acclaimed, but none was as surprising as his debut.

A Champion of Modernism, in Literature and Life

By Sophia Stewart

Margaret C. Anderson was at the center of a notorious literary-obscenity trial. Then she was forgotten.

What to Read

King of Kings, by Scott Anderson

Some events unfold so quickly, and overturn the status quo so completely, that they seem preordained. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 transformed the country almost overnight into a fundamentalist theocracy. But as Anderson, a war correspondent who has covered conflicts in the Middle East and beyond, shows in this thrilling account, nothing about the final months of the reign of the shah appears settled or inevitable. Drawing on government communiqués and first-person accounts—including that of a cantankerous American diplomat who seems to have witnessed every pivotal moment—Anderson describes a failure that had many fathers: not just the imperious yet indecisive Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, or the ruthless Ayatollah Khomeini, but also the useful idiots who surrounded the cleric, along with President Jimmy Carter’s fractious and communism-obsessed foreign-policy team. A catastrophe that reshaped the world, Anderson suggests, was enabled by people who couldn’t imagine how the world might change.

From our list: The Atlantic 10

Out Next Week

📚 Neptune’s Fortune: The Billion-Dollar Shipwreck and the Ghosts of the Spanish Empire, by Julian Sancton

📚 Beckomberga, by Sara Stridsberg; translated by Deborah Bragan-Turner

📚 Missing Sam, by Thrity Umrigar

Your Weekend Read

The Real Fight for the Smithsonian

By Lily Meyer

“The object of the museum is to acquire power,” announces a crusty old archaeologist in Penelope Fitzgerald’s 1977 satire, The Golden Child. It isn’t a goal he respects. He wants the museum where he’s settled into semiretirement to genuinely devote itself to educating its visitors. Instead, he correctly charges, its curators act like a pack of Gollums, hoarding “the art and treasures of the earth” for their own self-aggrandizement and pleasure.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Sign up for The Wonder Reader, a Saturday newsletter in which our editors recommend stories to spark your curiosity and fill you with delight.

Explore all of our newsletters.