When The Story Doesn’t Let Me Sleep: Sudipto Sen

deccanchronicle.com

Monday, February 16, 2026

When you speak to Sudipto Sen about his journey into cinema, it becomes clear that filmmaking was never a career choice in the conventional sense. It was an inevitability. Ask him when the “absurd dream” turned into a risk he was willing to take, and he reflects on his early years. “In a very e...

When you speak to Sudipto Sen about his journey into cinema, it becomes clear that filmmaking was never a career choice in the conventional sense. It was an inevitability.

Ask him when the “absurd dream” turned into a risk he was willing to take, and he reflects on his early years. “In a very early stage I understood that I can't do anything but to tell stories,” he says. That certainty was forged in North Bengal, where he grew up during the turbulence of the Naxalite movement. “It was a very very difficult time… Bengal was the epicenter of that,” he recalls. The socio-political unrest reshaped institutions, public life and cultural spaces. Between what he calls the “rich Bengali tradition” and the violence of an ultra-left uprising, his worldview was being formed.

“With all obvious reason I thought that I have to tell my stories, how I see the world, how I see the life which I am leading to.” Watching world cinema in Kolkata further sharpened that instinct. By the time he finished his studies, he already knew the destination. “I knew that one day I have to become a filmmaker and I did that.”

His academic path was deliberate. He studied physics as an undergraduate and later pursued applied psychology. To him, they are deeply intertwined. Physics is “the philosophy of science,” while applied psychology is “an extraction of human philosophy.” Both, he believes, are essential to cinema. “These are very very intriguing subject interconnected and it has lot to do with your invocation as a filmmaker.” Understanding matter and understanding the mind became twin pillars of his storytelling grammar.

The Himalayas played an equally formative role. His debut feature, The Last Monk, emerged not from a neatly outlined story but from lived experience. “You will be surprised to know I never wrote a story at all. I straight wrote the script,” he says. He had spent nine months travelling on foot from Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh, covering nearly 3000 kilometres. “Unless that evolved in your own organic system, it is not possible to do that.” The mountains became both backdrop and metaphor, returning in ‘Akhnoor’ and other Indo-French collaborations. “Himalayas has a major role in my construction,” he says simply.

Years later, ‘The Kerala Story’ would catapult him into national debate. But for Sen, the intention remained unchanged. “I have no intention to talk about anything other than the stories of those girls.” He followed the subject for almost a decade, travelling repeatedly, interacting extensively. “I met more than 3000 girls… I had no other intention but to tell those stories.”

Political readings, he insists, were not his design. “A story which touched my heart, I try to tell the story. And in that process, if it charted the territory of politics… it is coincidental. I don't plan that way.” For him, storytelling is instinctive rather than strategic. “The story influenced me. Don't let me sleep. I make films on those stories.”

Sudipto Sen

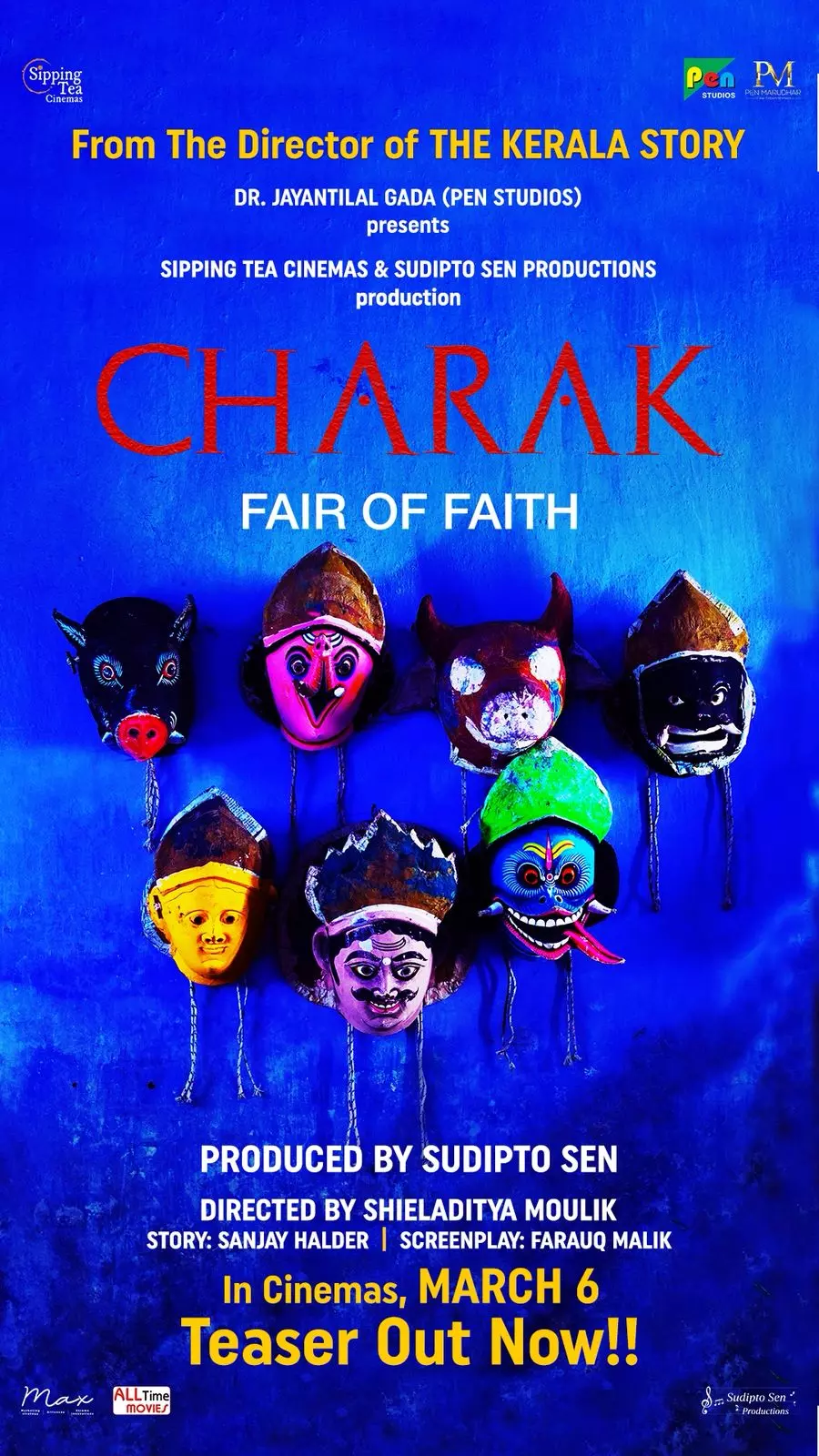

That instinct continues with his upcoming film, ‘Charak’. Even before release, the film has drawn reactions. “Many people are saying ‘Charak’ will be another controversial film,” he notes, but remains unmoved. “I thought that this story should be told.”

‘Charak’ takes its name from one of Bengal’s largest festivals, celebrated in parts of eastern India with colour, music and devotion to Kali and Shiva. But alongside the celebration, Sen examines the darker strands that have historically attached themselves to ritual: obscurantism, occult practices and extreme superstition. “Superstition is very much part of our organic life,” he says. The film explores how civilizations confront such darkness and attempt to move towards light. For him, it is not about provocation but about observation.

Recognition has altered his professional landscape. Winning the National Award has made him feel “more responsible” and at the same time “liberated.” Greater visibility means greater scrutiny, but it also brings easier access to finance and scale. More importantly, it has deepened his commitment to what he calls Indian cinema. “In India, Indian story is very rare. Indian cinema is very rare,” he says, pointing out that although thousands of films are produced annually, few endure in memory. “On Monday, everybody forgets.”

He speaks about cultural erosion and the loss of originality. Audiences, he suggests, are often more comfortable consuming borrowed idioms than rooted narratives. Cinema, like all art, must return to authenticity. “You are most comfortable in your mother's lap. So, the moment you are taken away, you become vulnerable.” For him, storytelling must come from that intimate space.

International collaborations have enriched his craft. A student of European New Wave cinema, he views filmmaking as an act of stimulating the human brain. Editing rhythms, camera sensibilities, narrative minimalism, all feed into how audiences process images and emotion. He cites the Iranian classic Children of Heaven as an example of pure storytelling triumphing over scale. A simple narrative about siblings and a lost pair of shoes, yet powerful enough to hold viewers without spectacle.

“Human brain stimulation, it is a science,” he says. International collaboration, for him, is a way to absorb the best techniques while staying rooted in personal truth.

At his core, however, the philosophy remains unchanged. He does not set out to create political cinema, social cinema or romantic cinema. “I just tell the story the way it happened to me.”

And when a story refuses to let him sleep, that is when he knows it must be made.

Read the full article

Continue reading on deccanchronicle.com